Creating Enduring Competition in the Search Market

Since the ruling in the U.S. v. Google search case was announced, there has been discussion about how to remedy Google’s dominance. As a company that operates a search engine that directly competes with Google, we have several ideas about how to craft a set of legal and technical interventions that can, in combination, effectively curb the advantages Google has gained through illegal use of their search monopoly. DuckDuckGo believes it is possible to put remedies in place that will establish enduring search competition, encourage innovation and new market entrants, and result in significant market share among multiple competitors.

However, there is no silver bullet remedy that, alone, will adequately address both Google’s scale and distribution advantage as well as ensure that Google cannot circumvent its obligations. Instead, the “remedy” must be a package of remedies that work together to effectively counteract the unlawful competitive imbalance.

Counteracting Google’s Scale Advantage with Access to Search Results

Many ideas on the table aim to counteract Google’s distribution advantage, but we believe it’s equally important to address Google’s scale advantage. Google’s exclusive default distribution deals mean they see way more queries than everyone else, a.k.a. their scale advantage. The court’s opinion quantifies this disparity:

More users mean more advertisers, and more advertisers mean more revenues…. Google’s scale means that it not only sees more queries than its rivals, but also more unique queries, known as “long-tail queries.” To illustrate the point, Dr. Whinston analyzed 3.7 million unique query phrases on Google and Bing, showing that 93% of unique phrases were only seen by Google versus 4.8% seen only by Bing.

Google uses this stream of information to continuously improve their results by running large-scale experiments in ways that no rival can because we’re effectively blinded. Google infers the best results based on queries it has seen before. If a search engine sees fewer – or often zero – similar queries, these inferences are less effective.

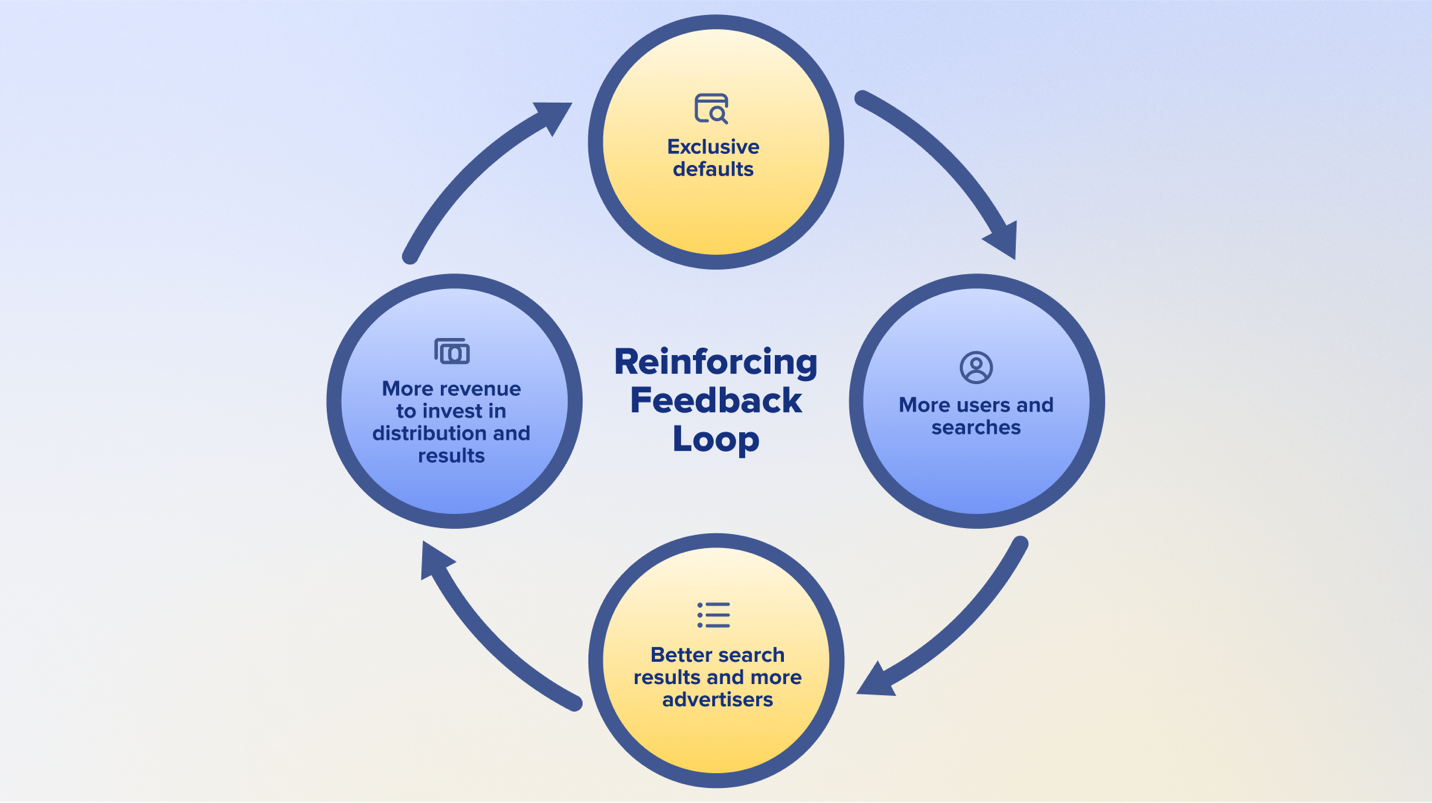

As the court describes the situation, Google’s scale advantage fuels a powerful feedback loop of different network effects that ensure a “perpetual scale and quality deficit” for rivals that locks in Google’s advantage.

Google’s exclusive defaults are part of a reinforcing feedback loop that gives them an insurmountable scale advantage and makes it difficult for rivals to compete.

The best and fastest way to level this playing field is for Google to provide access to its search results via real-time APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) on fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms. That means for any query that could go in a search engine, a competitor would have access to the same search results: everything that Google would serve on their own search results page in response to that query. If Google is forced to license its search results in this manner, this would allow existing search engines and potential market entrants to build on top of Google’s various modules and indexes and offer consumers more competitive and innovative alternatives.

Today, we believe that we already offer a compelling search alternative with more privacy and fewer ads, relative to Google. We’ve also been working for fifteen years to make our search results on par in terms of feature set and quality by combining our own search indexes with those of partners like Apple, Microsoft, TripAdvisor, Wikipedia, and Yelp. However, we know that many consumers still prefer Google’s results due to the benefits of scale discussed above, and this intervention would erase that advantage, instantly making us and others much more competitive.

We’ve already seen some concerns about this remedy direction that we’d like to quickly address. First, licensing Google’s search results does not involve accessing any user data. This remedy will not invade user’s privacy, which is aligned with our vision as a company. We know from experience that this remedy can be implemented anonymously, and we can advise on that implementation. We can open up Google without opening up user data.

A second potential concern is that long-tail results on leading search engines could be similar in some cases, but that’s a feature not a bug. Google’s scale advantage gives them insights into which obscure links should be ranked higher, and so we should expect that when smaller search engines incorporate this information that some results would become more similar. However, licensing on FRAND terms should also allow competitor search engines to re-rank and mix results with other content, which will enable competitor search engines to produce different ranking algorithms based on the same underlying high-quality search results.

Additionally, FRAND licensing will allow other search engines to more competitively differentiate on things like privacy, design, and customization of the user interface and results page, while still providing high-quality results. For example, we can envision a universe of differentiated and innovative experiences, such as features that allow users to tweak ranking algorithms, features that bring more transparency to ranking algorithms, and other AI capabilities, all leveraging Google’s search result APIs. Future-looking use cases like these must be kept in mind, and FRAND API access is what is needed to power these types of search innovations.

A third concern is that competitor indexes could become too reliant on Google; however, if all the results that come through the APIs can also be used as an input into building search indexes, this would ensure that there is also a path to long term viability and independence for competitors. We, for one, would go further down this path. This could be accelerated if the APIs also provide access to Google’s anonymous ranking signals (for example, how often and quickly people in aggregate click back after visiting a link), which will help tune competitor indexes even faster as well as improve real-time reranking algorithms. That said, we recognize that licensing Google’s search results needs to be a long-term intervention because their scale advantage will persist as long as Google has much more significant market share than competitors.

There are historical precedents for this type of remedy as well. AT&T’s 1956 antitrust agreement required the company to license its patents on FRAND terms, which allowed existing and new companies to build on top of AT&T’s innovations. Similarly, the Telecommunications Act of 1996 encouraged competition in communications markets by requiring large telecommunications providers to interconnect their networks with new competitors on FRAND terms.

This is not a new technical challenge for Google either: Google already licenses their search results, including their ads, via real-time APIs to some competitors. It’s also not novel in antitrust, as API access was at stake in Microsoft’s antitrust settlement two decades ago. An API-based remedy also means that startups could immediately enter the search market rather than be forced to invest tens or hundreds of millions of dollars upfront to get started by acquiring and consuming massive data sets. It also protects nascent competition in AI-driven search by allowing them to use the APIs to ground answers in real-time.

Finally, we should note that the EU’s Digital Markets Act attempts to solve Google’s scale advantage by requiring Google to provide FRAND access to its “click and query data.” To date, this has been ineffective because Google has undermined the requirement by limiting the data they share to the point of being useless. However, while we believe that click and query data is not a substitute for FRAND access to search result APIs, we also believe that if implemented correctly it can complement and further accelerate the path to competitor independence. That’s because API access will be limited to queries a competitor search engine actually sees, whereas click and query data can be much broader, covering almost all the queries Google sees. Therefore, access to this data in a privacy-protective manner should also be given on FRAND terms.

Counteracting Google’s Distribution Advantage with a Ban on Self-Preferencing in Chrome and Android

Google likes to claim everyone chooses Google, but most consumers don’t: they just go with the default. The court outlines how staggering this default advantage is:

50% of all queries in the United States are run through the default search access points covered by the challenged distribution agreements…. An additional 20% of all searches nationwide are derived from user-downloaded Chrome, a market reality that compounds the effect of the default search agreements. That means only 30% of all [general search engine] queries in the United States come through a search access point that is not preloaded with Google. Additionally, default placements drive significant traffic to Google. Over 65% of searches on all Apple devices go through the Safari default. On Android, 80% of all queries flow through a search access point that defaults to Google.

The court also consolidates evidence highlighting that large percentages of consumers don’t even realize they are using Google because of these defaults:

- An internal Google email in 2016 acknowledged that “users on Edge don’t even realize they aren’t using Google.”

- A 2018 Google study revealed there was “substantial user confusion regarding which browser and [general search engine] was in use.”

- A 2020 Google study found that over 50% of U.S. iPhone users were “unsure” what search engine powered Safari, concluding users are “often unaware they’re using Google.”

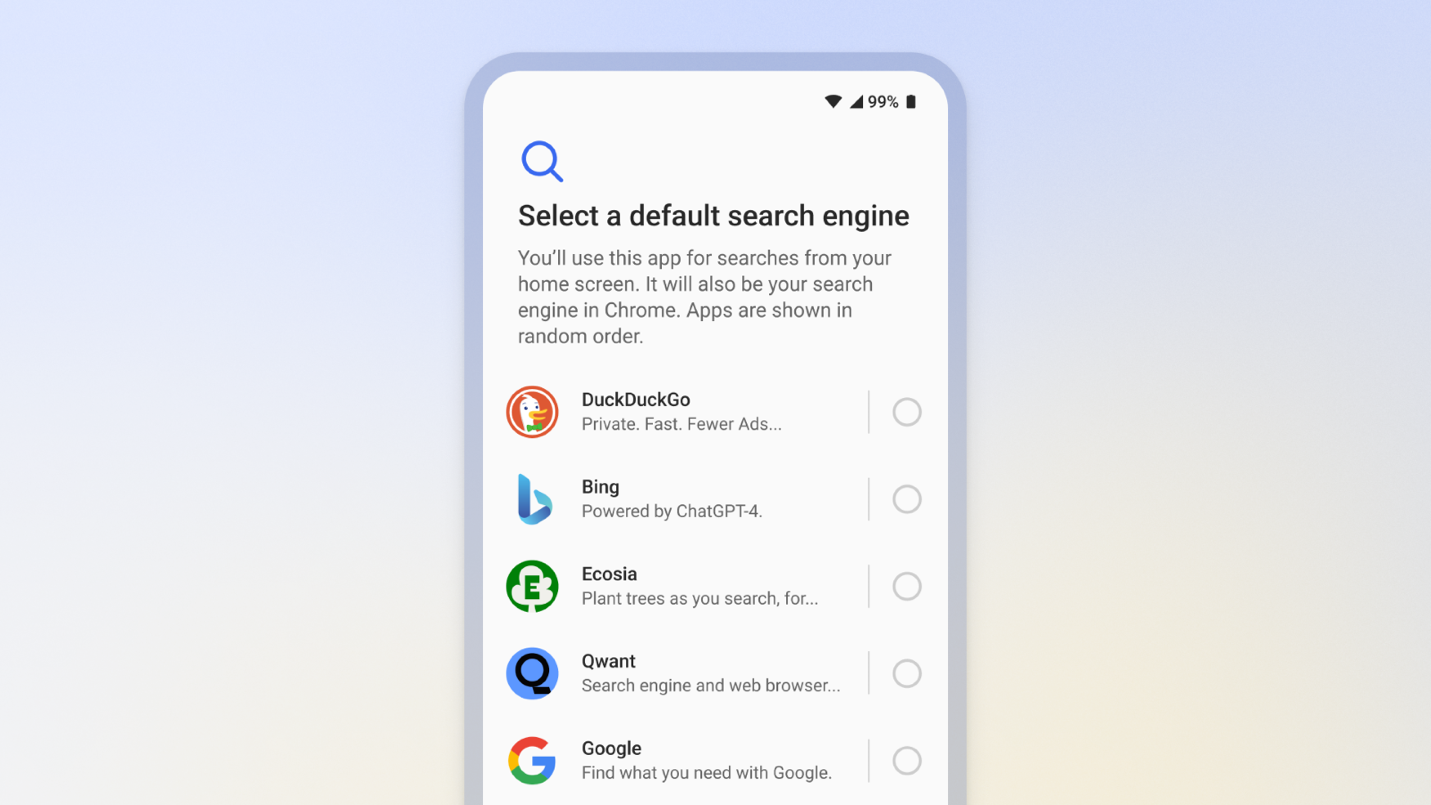

Users are confused and competition is crushed. As a result, Google shouldn’t be able to self-preference its search engine on Chrome and Android, which were developed to expand the reach of Google Search. Within these products, there should be no preset search default. Instead, these platforms need user-friendly settings based on sound principles that provide for:

- Regular access to well-designed choice screens that put users in charge of choosing their search engine default when setting up Android or Chrome, and periodically thereafter. Choice screens should set the search engine across all search access points on Android and Chrome.

- An easy way for users to navigate back to these settings.

- A one-click mechanism for any rival search engine to switch these settings and offer itself as a default search engine when users visit their website or app.

Image of the search engine choice screen on Android in the EU.

Banning self-preferencing must also include a prohibition on dark patterns, and all remedies must be subject to anti-circumvention provisions. For example, these restrictions should prohibit Google from discouraging users from installing rival apps or search extensions, or encouraging them to switch back to Google.

Unfortunately, a self-preferencing ban won’t create enduring competition by itself. However, as rivals can innovate on top of Google’s search results, and consumers become aware of rival brands and their increased quality, this increased access to consumers will accelerate competition in the search market.

Counteracting Google’s Distribution Advantage by Restricting Exclusionary Contracts

The court has already declared Google’s exclusionary contracts unlawful. While there are methods outside of these exclusive defaults to access search engines, the court recognizes that these “channels are far less effective at reaching users. That is due in part to users’ lack of awareness of these options and the ‘choice friction’ required to reach these alternatives.”

Restricting these exclusive agreements is therefore essential to help open up access to the search market. However, just restructuring these contracts by itself won’t do much because it won’t directly counteract Google’s entrenched advantage. For that, we need to look to the remedies discussed above.

On Accountability

Even the most well-crafted remedies will ultimately fail if Google is in charge of designing and implementing them, as has been the case in the EU. We’ve seen firsthand how Google has easily and repeatedly avoided complying with both the letter and the spirit of the law. Consequently, an independent monitoring body made up of technical experts and affected market participants must be fully empowered to keep Google honest. We should expect that this monitoring entity will need to be in place for as long as the remedies are in place. We cannot let the fox guard the henhouse.

On Structural Remedies

We are not opposed to structural remedies, but they would need to be paired with the additional interventions outlined in this post. In other words, structural changes to Google could theoretically be an accelerant in some circumstances, but regardless are not a replacement for FRAND access to search results and click and query data together with a ban on Google-self preferencing and a restriction on exclusive contracts. And we can envision some scenarios where a particular structural remedy could be more harmful to us than helpful.

A Long Road Ahead

Counteracting the entrenched competitive imbalance that Google’s default advantage has afforded them will not happen overnight. Realistically, it will take years for competition to take hold, and a fully-funded and motivated Department of Justice will need to be involved for the long haul. However, we are confident that a package of well-implemented and carefully monitored remedies, each designed to address a specific choke point, can work to create enduring competition in the search market.